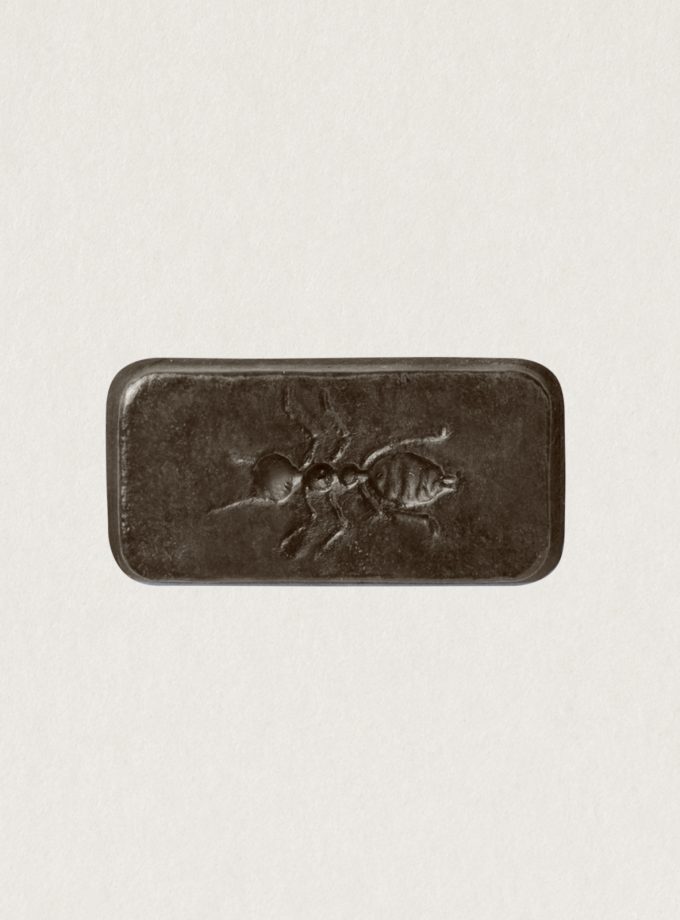

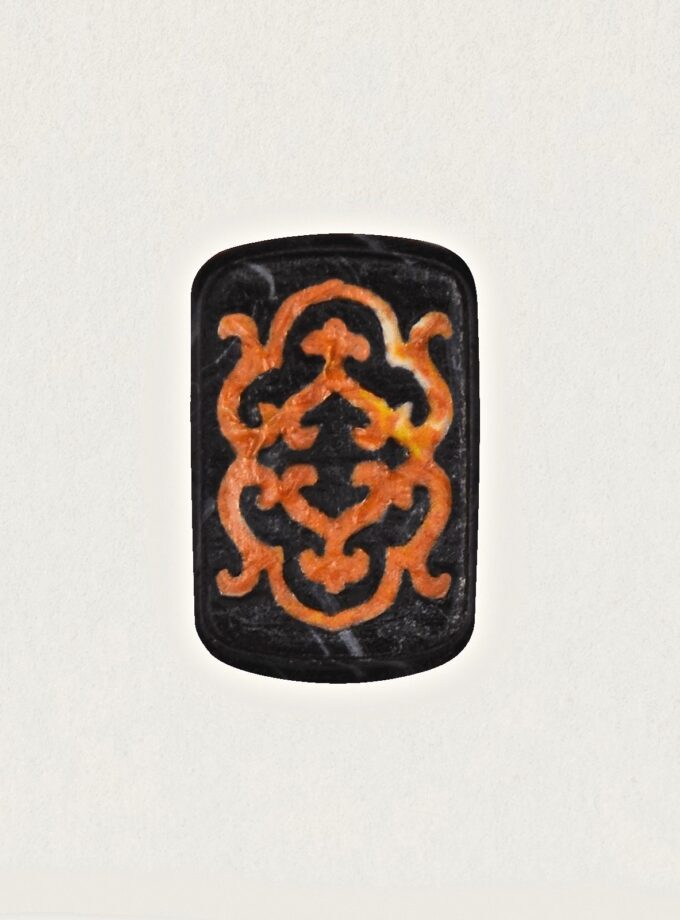

Ant

The Ant was considered sacred in both ancient Greek and Roman cultures. The Greeks worshipped Myrmex, a goddess in the form of an ant, the Romans the goddess Cecere, who’s main attribute was the ant. A symbol of hard and untiring work for the common good, the Ant has tremendous physical strength and resistance at the service of the community. The Ant embodies the promise of success achieved through commitment.

Source: Roman, red jasper intaglio, Private Collection

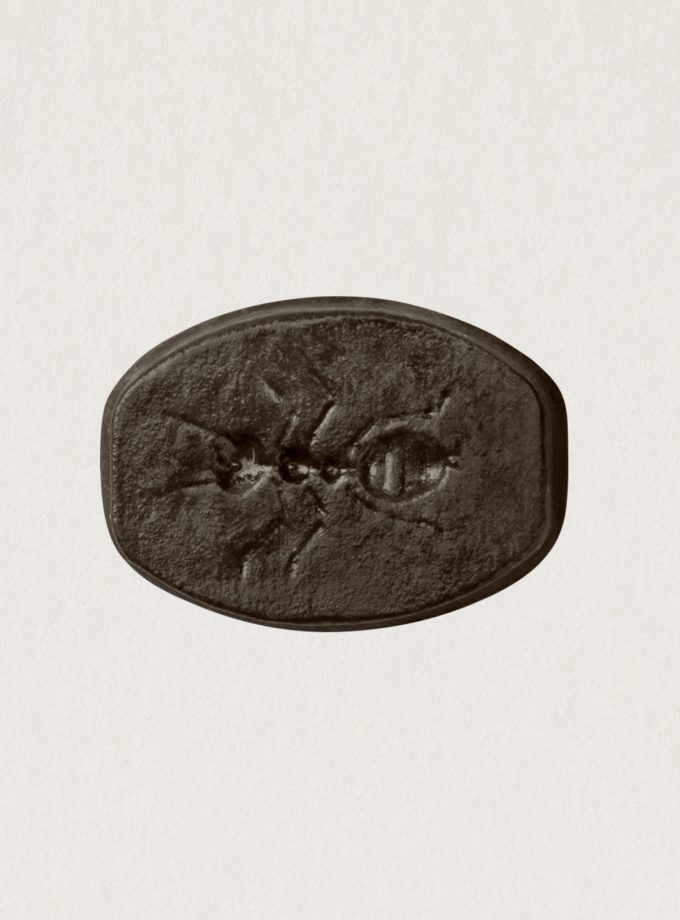

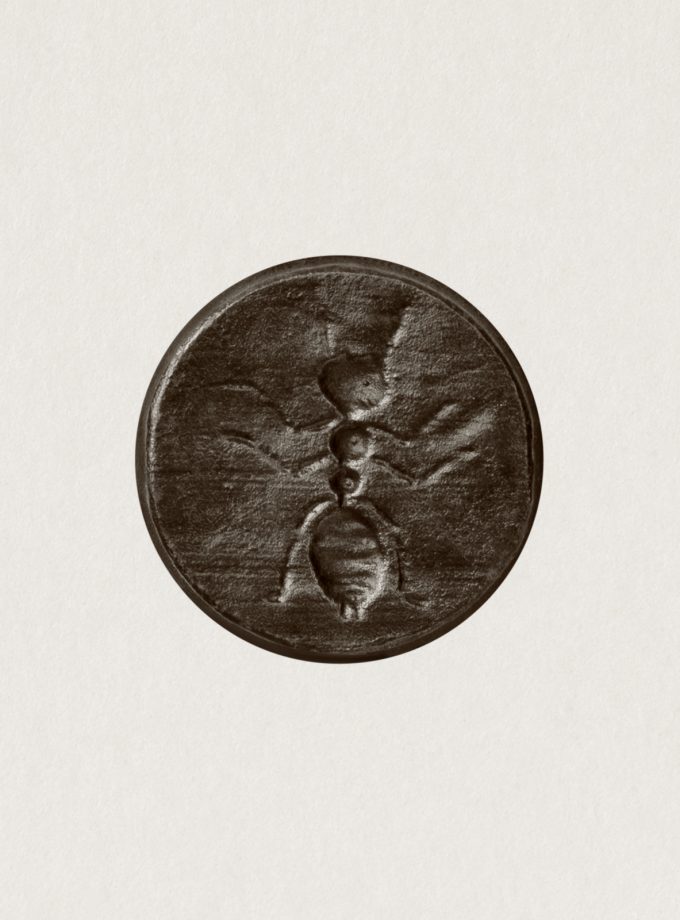

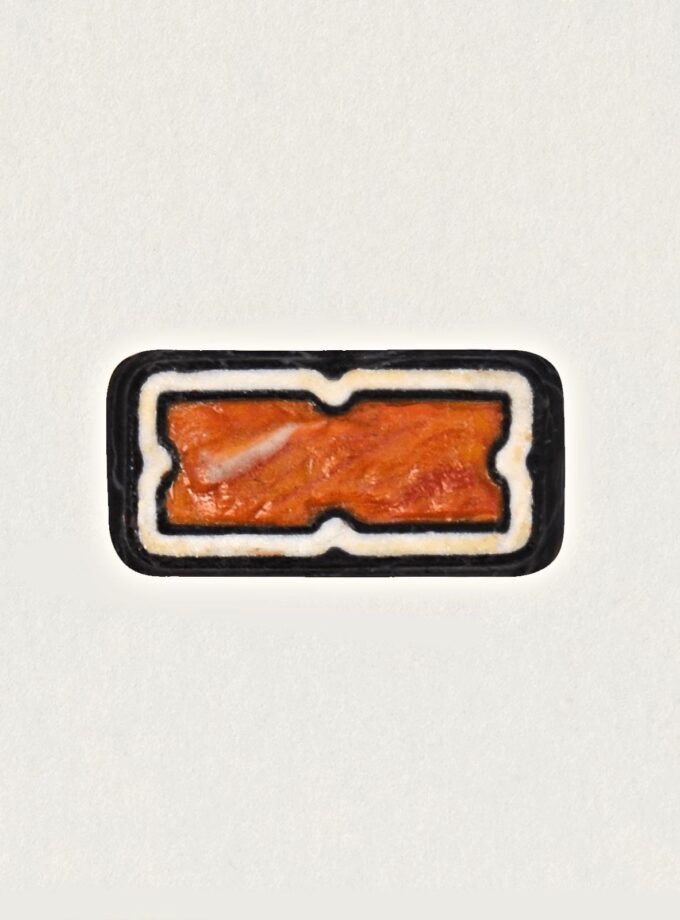

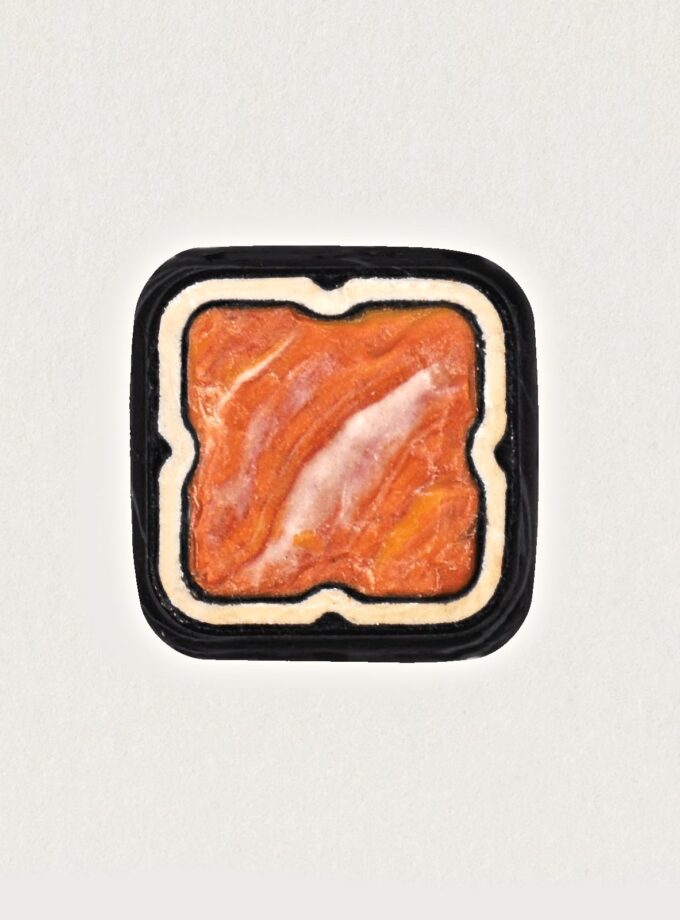

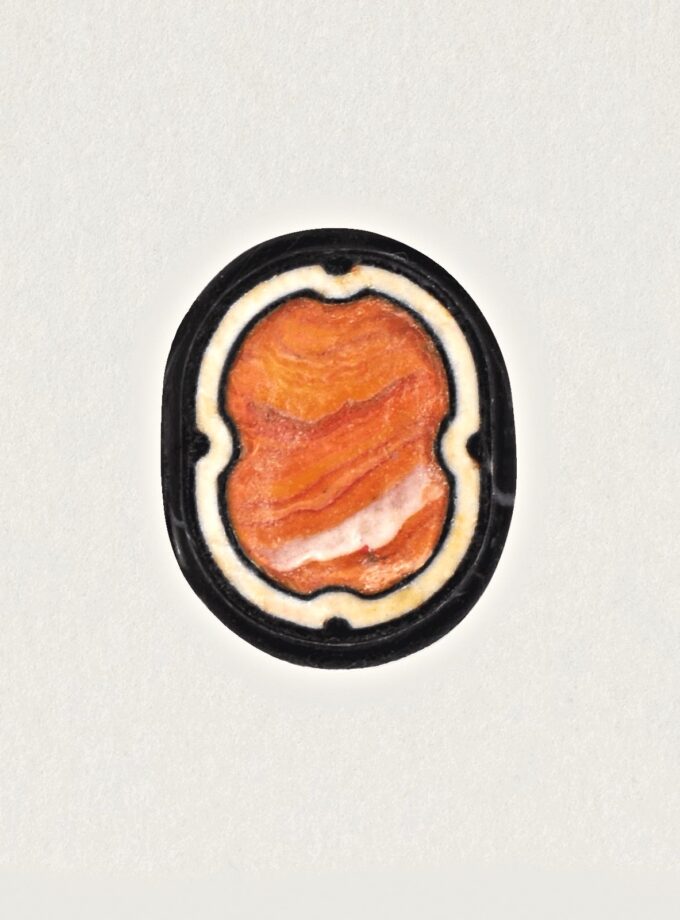

Bee

The Bee has always been an endless source of mythological, esoteric, political and religious symbols. It is part of a well-structured and efficient society. Relentless, its role – that the Romans already described as fructuosus – is to work for the good of the hive, the community. Its tireless activity transforms pollen into honey – used to make Ambrosia, a sacred beverage in many antique cultures – and it also produces wax, at the base of many religious objects. Its custom to withdraw in winter and appear again in the spring has made the Bee the emblem of regeneration, of the eternal cycle of life and death. To past symbolism we can now add the bee’s newly discovered role as an extraordinary biological indicator, signaling chemical damages to the environment and therefore of the potential risks to mankind.

Roman, Carved intaglio gemstone, 1st-3rd century, Yale University Art Gallery

Etruscan Granulation

The VII century B.C. Etruscan tombs have given us back many precious artifacts decorated through the granulation technique, an art already in use in the second millennium BC and which had been introduced in central Italy by eastern civilizations during the Orientalizing period. The Granulation method consisted in the welding of spherules or granules of precious metal on a surface, creating geometrical motives or figurative patterns. After the Roman colonization of the Etruscans, this technique disappeared together with the relevant and complex know-how to reproduce it. In spite of the numerous attempts to recuperate this art throughout history, the excellence of the Etruscan craftsmanship has never been reached.

Source: Bernardini and Barberini Tombs, second half of VII century BC, Museo di Villa Giulia, Rome

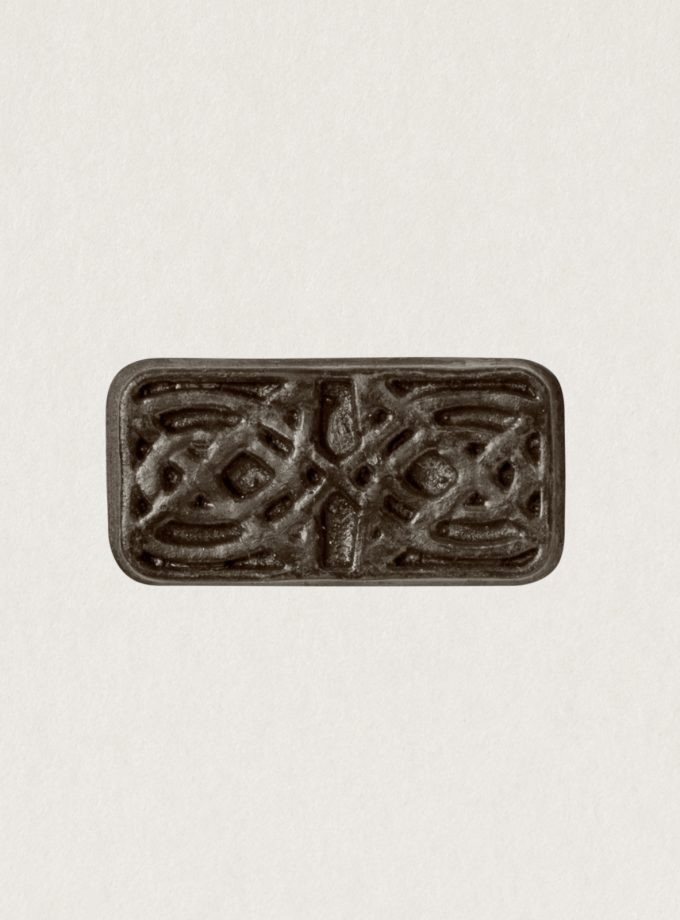

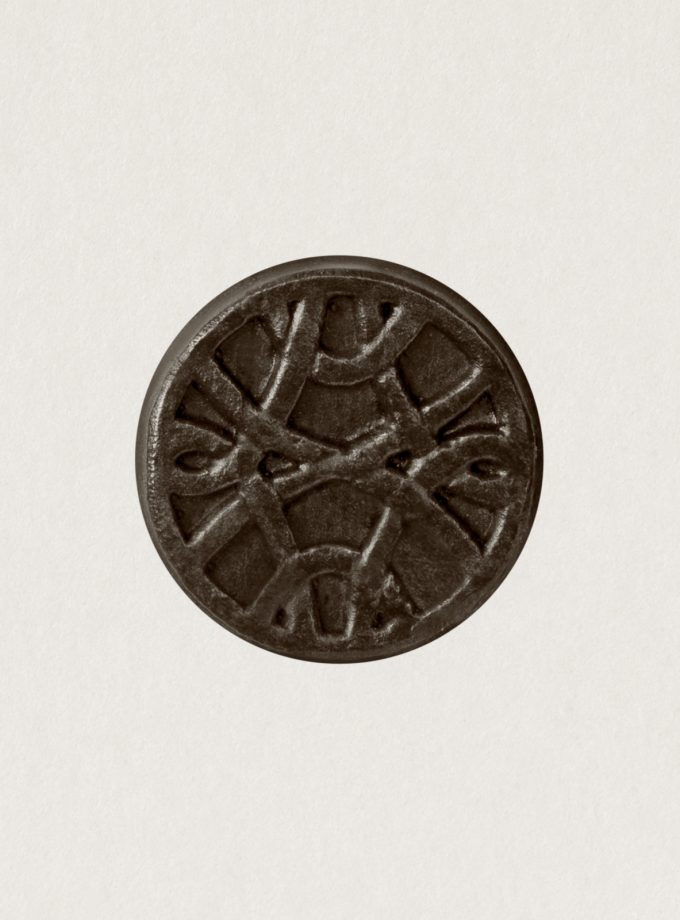

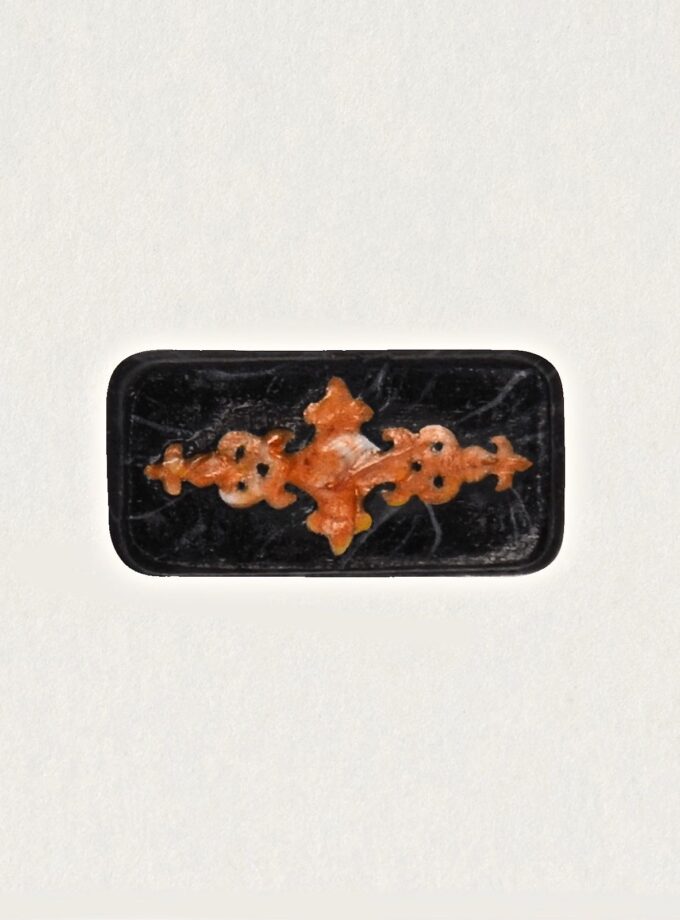

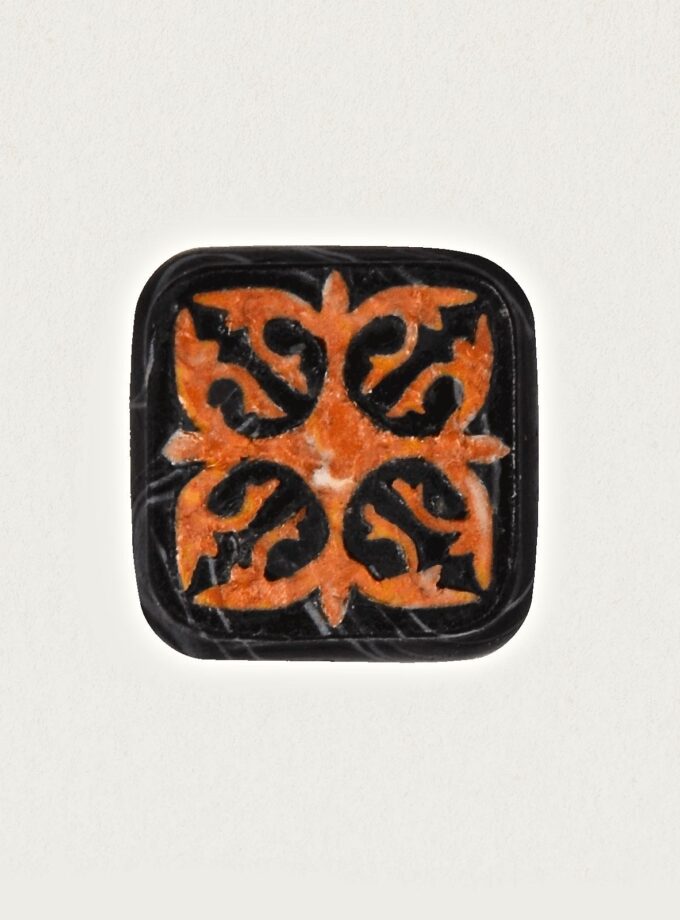

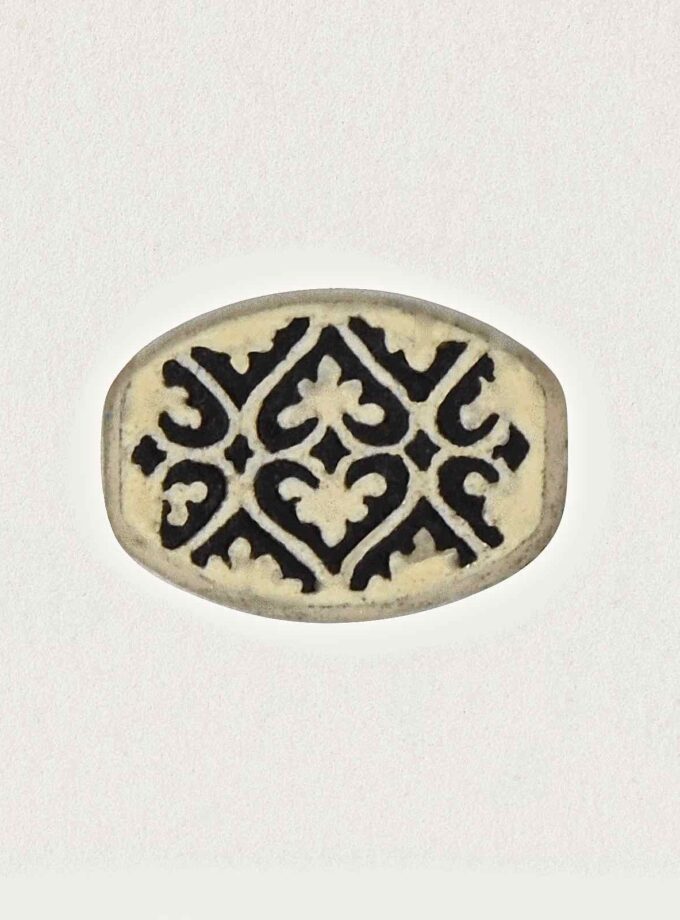

Interlace

The Interlace motif, already in use in Classical Art and even earlier in Ancient Oriental Art although as a minor décor element, becomes preponderant in late antiquity, when naturalistic elements are slowly replaced in favor of a purely decorative and geometric ornamentation. A trend towards a more rigorous order of forms, typical of the Carolingian art, was already visible in the Italian late Longobard sculpture, favored by a tendency to replace the representation of the human figure with abstract motives, especially in religious contexts.

Source: Late Longobard plaques, VIII century, Museo Cristiano di Cividale, Basilica Patriarcale and Museum of the Monastery of Aquileia

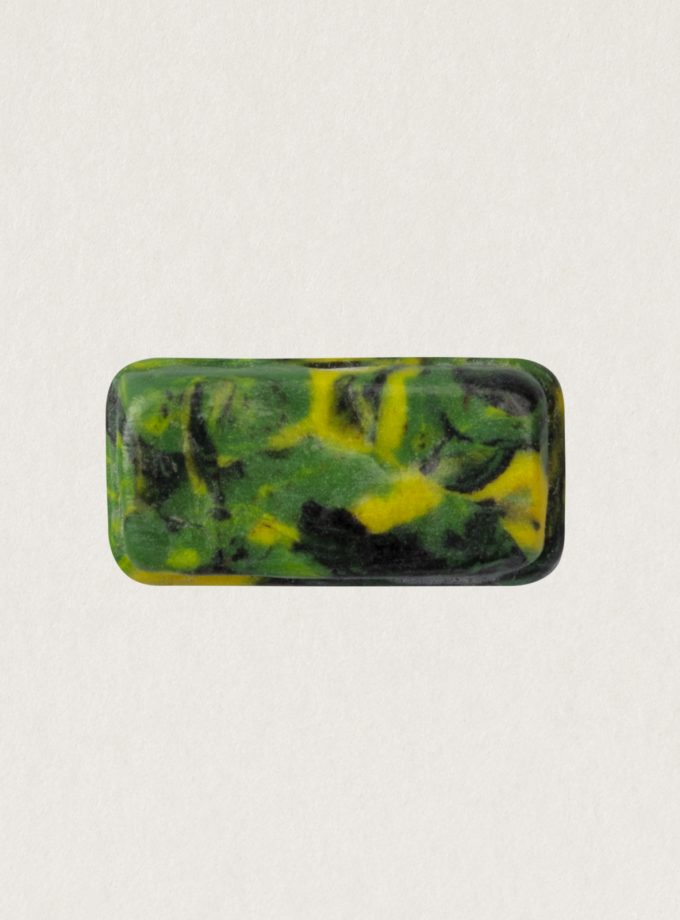

Marble

In the late Republican era and especially later during the Roman Empire (1 century AC), the use of polychrome marble became predominant for the decoration of public and private buildings. Huge quantities of marble were imported from the conquered territories. Red porphyry, green serpentine, antique yellow and pavonazzetto were cut in plaques in order to create engravings (opus sectile) for pavements and walls.

With the economic crisis of the Empire, the spreading of Christianity and the increasing cost of import, older buildings were slowly stripped of their precious marbles which were reused for the decoration of new churches and palazzos in Rome.

The word “marble” comes from the Greek màrmaros, or resplendent stone.

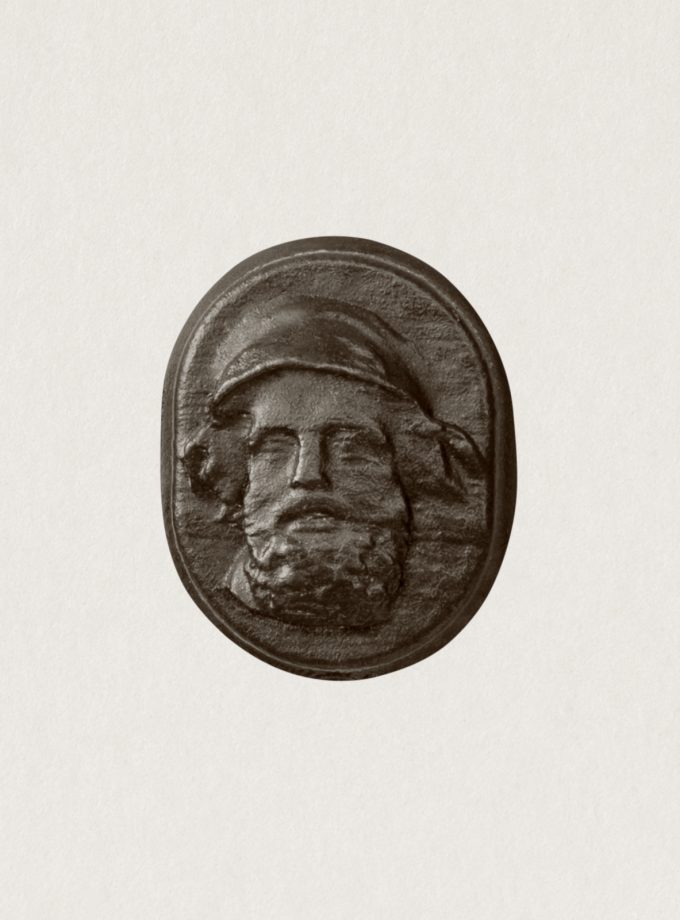

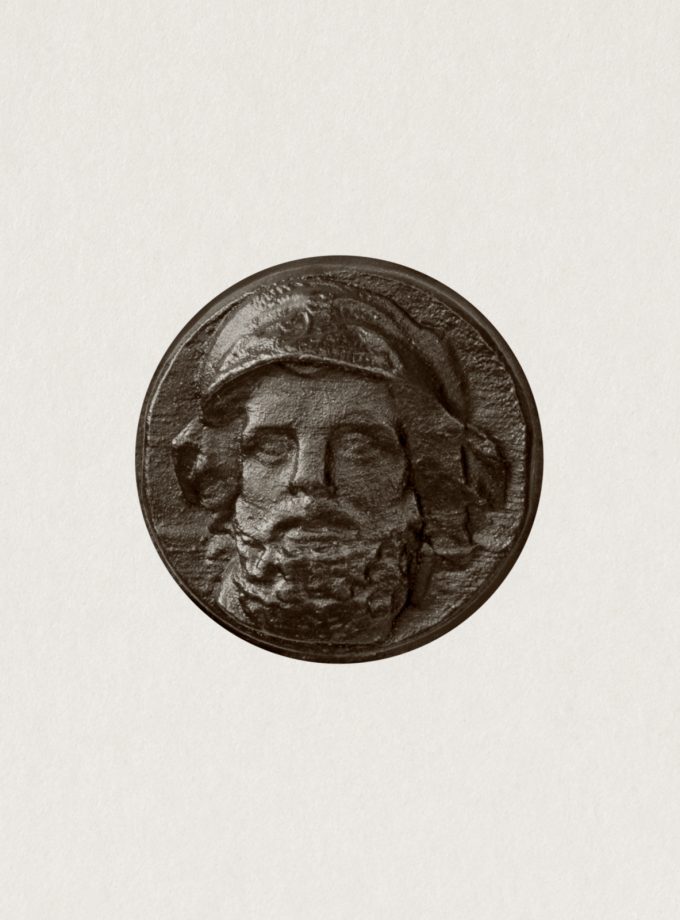

Menelaus

Menelaus is a hero of the Greek mythology and a prominent character in Homer’s Iliad. King of Sparta, husband of Helen, hero of the Trojan war, Menelaus is glorified for his great beauty and for his valor on the battlefield.

The bust here reproduced, a Roman copy of the 2nd Century AD, was found in Villa Adriana, Tivoli, at the end of the 18th Century and bought by Pope Clemente XIV for the Vatican Museums where it is still preserved.

Know as part of the so called Gruppo del Pasquino, there are several copies of this subject representing Menelaus holding Patroclus’ dead body. Beside the fragment still visible today in Piazza Pasquino which had been found in the nearby Stadio di Domiziano, now Piazza Navona, a few other replicas today are kept in Florence: one in Palazzo Pitti, discovered in Rome’s Mausoleum of Augustus and the most famous exemplary visible at the Loggia dei Lanzi in Piazza della Signoria in Florence, found near Rome’s Porta Portese, at Caesar’s gardens.

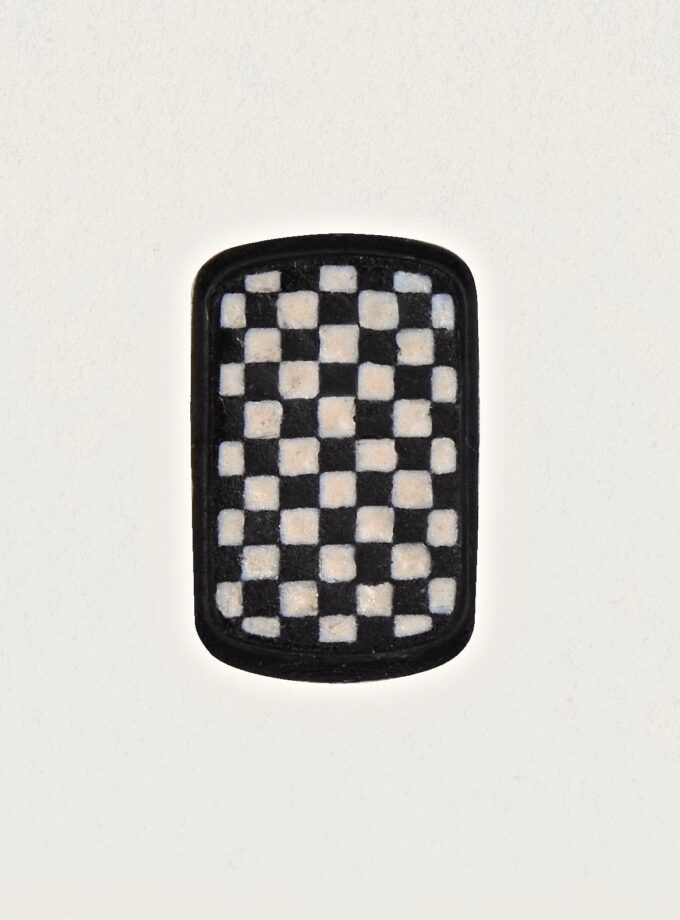

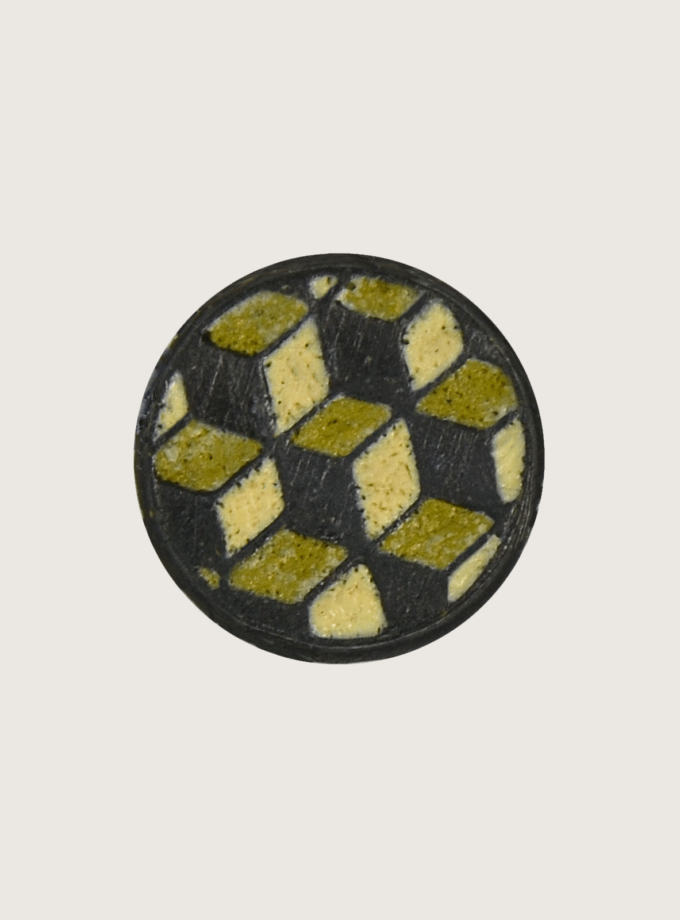

Mosaic

Opus tessellatum in Latin, mosaic is a technique that involves the use of tesserae – small cubes of stone, marble, glass, ceramic or other hard material of uniform size – applied to a surface to form ornamental and geometric patterns. This technique is often used in parallel with opus sectile – which only foresees the use of larger marble slabs – as can been seen in the floors of the San Marco Basilica in Venice. The first examples of homogeneous opus tessellatum with same-size tesserae trace back to early 2nd century B.C.

At the end of the 1st century B.C. a new trend takes over and black and white mosaic becomes the prevailing technique at least until the second half of the 2nd century A.D, due to lower cost of implementation.

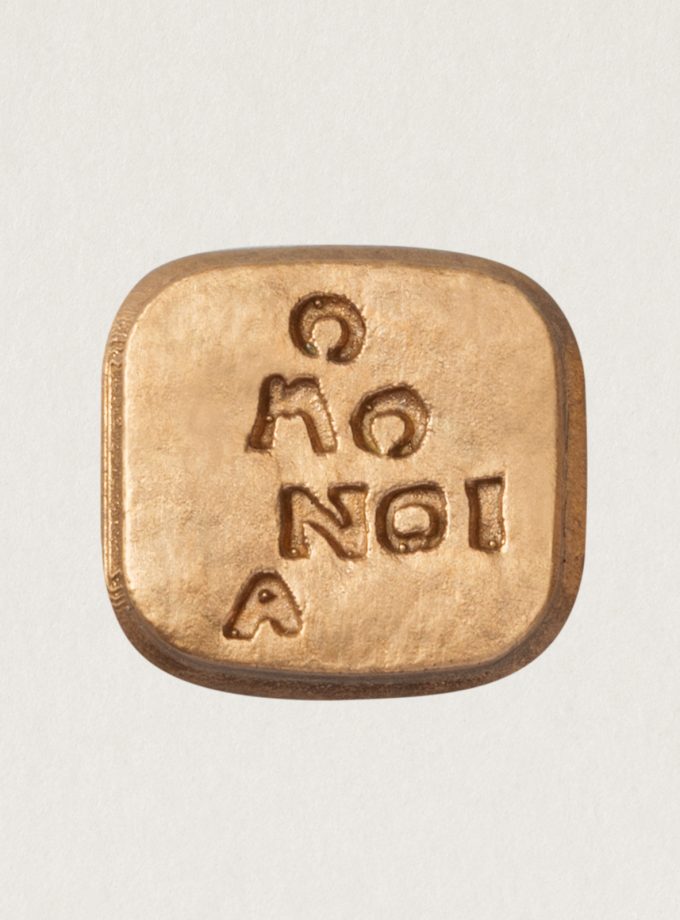

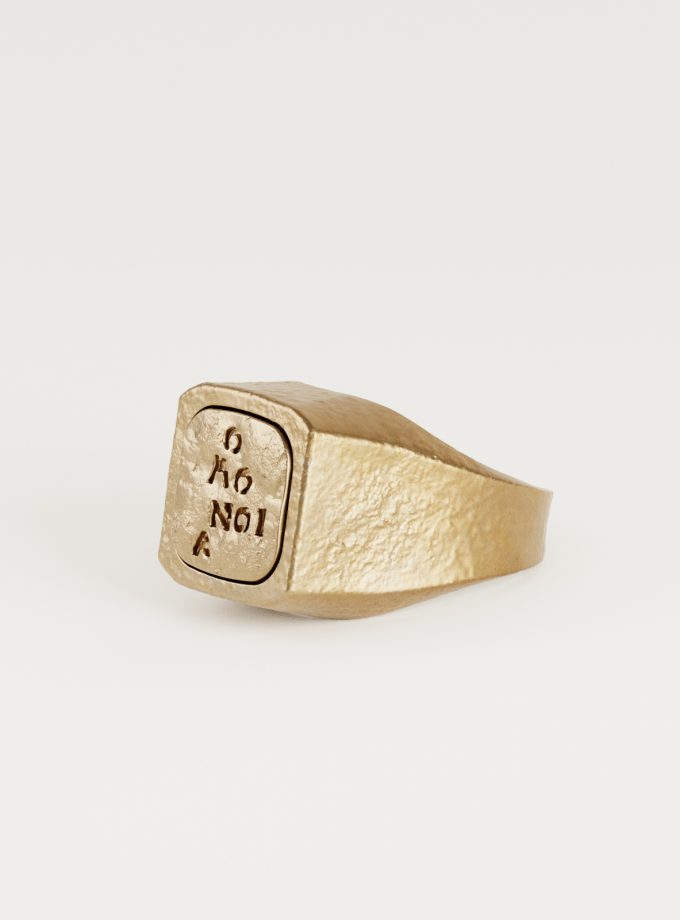

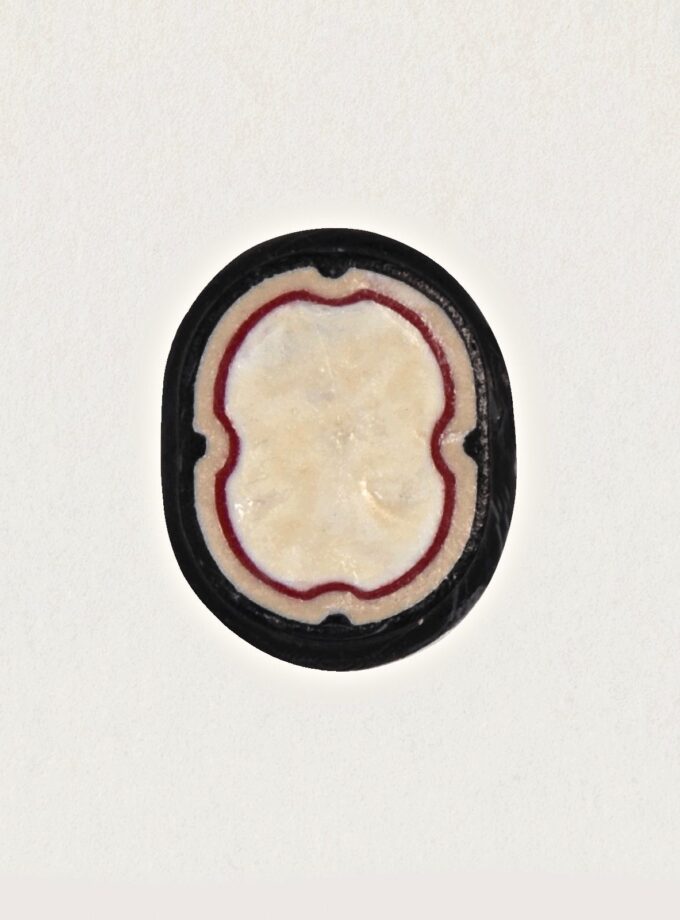

Omonoia

The Greek word Omonoia expresses the natural and legal bond at the basis of a community and its civic coexistence. Hellenistic as well as Roman Imperial coins represent Omonioa as Concordia, a Roman goddess symbolizing political unity or also a family bond as well as the love between spouses. On other Roman artifacts of the Imperial Age, Omonoia is depicted as a dextrarum iunctio, two clasped right hands indicating a form of agreement and the inscription OMONOIA, or sometimes just through the simple lettering.

Source: A fifth-century Byzantine gold and agate cameo ring with clasped right hands (dextrarum iunctio), Private Collection

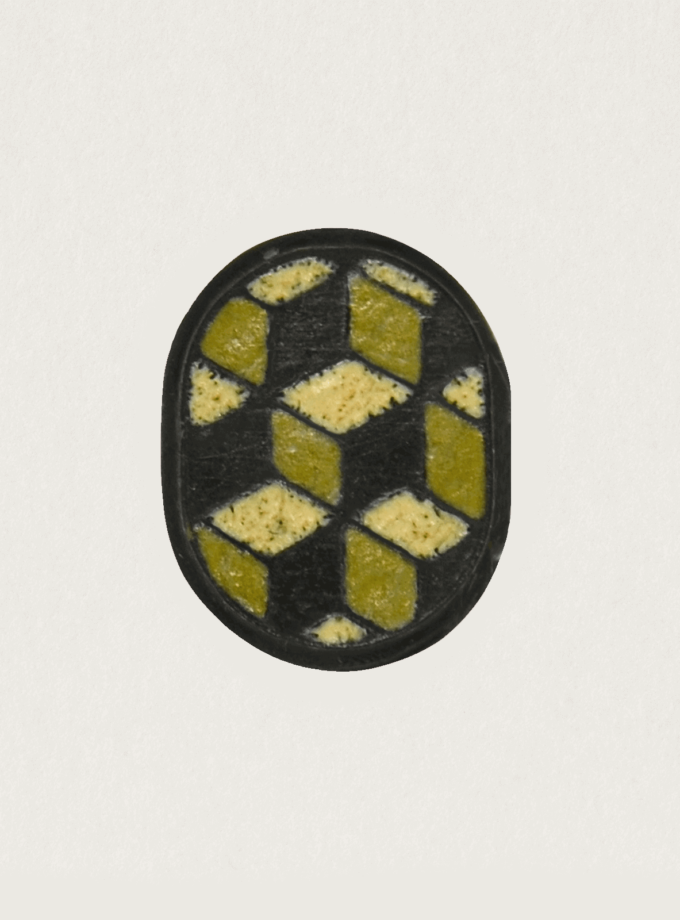

Opus Sectile

Floor decorations created by small stone, marble or brick cubes laid to form a more or less complex design by color contrast, are defined as sectilia pavimenta by ancient authors.

Older sectilia pavimenta, composed of very small white, black or grey, green and red slabs of non-marble material begin to appear in the early 1st century B.C. They are typically formed by groups of three different color rhombuses, combined to create a hexagon and generate a tridimensional effect, such as in the House of Grifi on the Palatine in Rome or in Pompei’s Temple of Apollo.

Differently from the mosaic (opus tessellatum), opus sectile uses larger marble slabs selected by color, opacity and brilliance, to create compositions of rhombuses, triangles and squares, similarly to those created with the tessellatum technique.

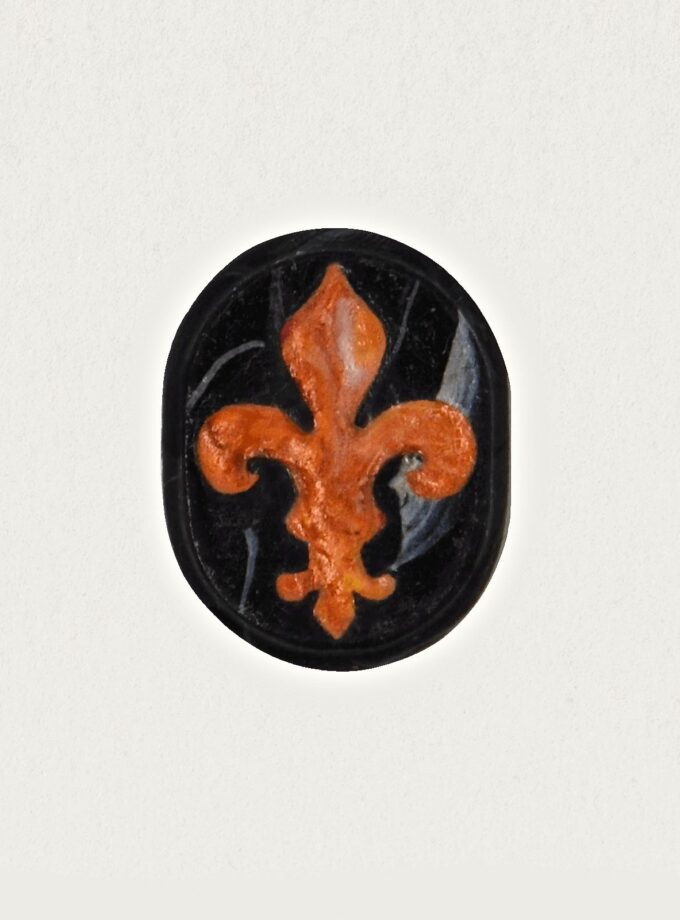

Pavimenta and Renaissance Inlays

In the last decades of the sixteenth century in Rome the taste for polychrome marbles is affirmed and powerfully manifests itself with the decoration of a large number of sacred buildings. While the choice of patterns is still strongly influenced by the past tradition, a wave of innovation towards new and unexplored forms takes place, favored by the availability of newly extracted marble which led to the creation of new color combinations.

Simple as well as more complex new geometric figures with inserts of curvilinear shapes and figurative forms derived from the world of heraldic and religious symbolism are achieved with the use of multicolor marbles for the walls, furnishing and floors. While white marble was employed to mark the outer lines of the original shape, widely used colored marbles had the task to disarticulate the space.

Raw

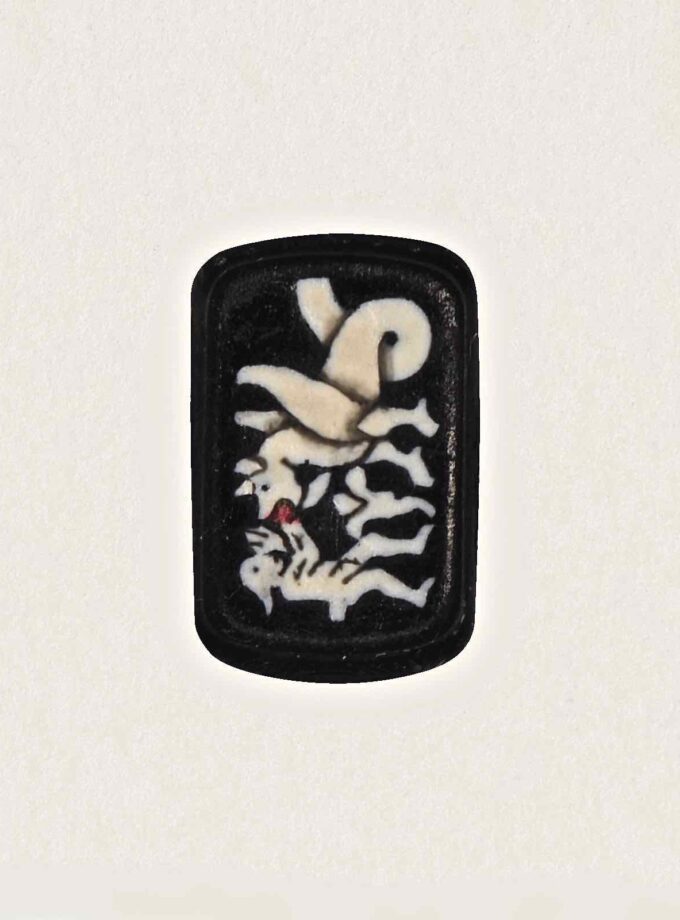

San Miniato al Monte

The Basilica of San Miniato al Monte in Florence was built between the 11th and the 13th century in a particularly evocative hill dominating position and it is considered one of the masterpieces of Tuscan Romanesque.

Its floors date back to 1207 when construction works were finally completed and show very precious black and white marble inlays in eastern style, geometric and zoomorphic patterns often inspired by fantasy animals as shown on textiles imported from the south-eastern Mediterranean. Geometric figures, stylized floral weaves, lions and rampant unicorns, hawks and doves, the Zodiac of life, they all lead the visitor from the main entrance to the center of the main nave.

Quite probably, these floors were created by the same masters who worked in the Baptistery of San Giovanni.

No products in the cart.

No products in the cart.